Filmmakers |

|

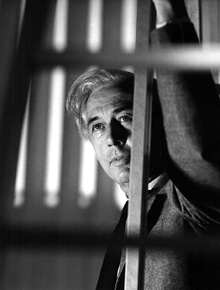

ROBERT BRESSON

ROBERT BRESSON When war broke out in 1939 Bresson enlisted in the Army. Captured in Holland when France was defeated in June 1940, Bresson wasn’t repatriated until March 1941. After his return to Paris he directed his first feature film Angels of the Streets (1943), which is about the Sisters of Bethany, a religious order devoted to the spiritual and moral rehabilitation of female convicts just released from prison. The dialogues were written by the famous French playwright Jean Giraudoux.

Encouraged by the success of this first film, Bresson undertook the adaptation of the story of Mme de la Pommeraye, the principal episode of an eighteenth-century French novel, Jack the Fatalist and His Master (ca. 1770) by Denis Diderot. With dialogues by Jean Cocteau, Bresson succeeded in making Ladies of the Park (1945) despite the enormous material problems posed by the end of the war and the battle for the Liberation of France. His film is a modernized version of Diderot’s story in which a society woman takes revenge on her unfaithful lover by tricking him into marrying a call girl. While critics will later recognize the many fine qualities of this film, Ladies of the Park is the greatest “failure” (the only film not to win any prizes) of Bresson’s career. The contemporary critics were generally severe, finding the film too dry, slow, and monotonous, the characters too inhuman and too cold to communicate the intense human passions at play.

Ladies is followed by a five-year period during which Bresson, working alone this time, wrote an adaptation of a novel by Georges Bernanos, Diary of a Country Priest (1936). The novel is about the solitary, agonizing path toward grace traveled by a young priest in a tiny rural community. Completed in 1950, the film was instantly acclaimed as an indisputable masterpiece. It won numerous awards and turned Bresson into an international celebrity.

After two failed projects at the beginning of the fifties — adaptations of the story of Sir Lancelot by the medieval poet Chrétien de Troyes and of Mme de Lafayette’s celebrated novel La Princesse de Clèves (1678) — Bresson read in a Parisian newspaper in 1954 the story of a spectacular escape from a Gestapo prison during the Occupation. This story will become the basis for Bresson's best-known film, A Man Escaped (1956). Although the adaptation of this true story was only the fourth feature film by Bresson in thirteen years, he had already become a kind of legend in the world of French cinema. Bresson has both detractors and hard-core supporters, but the latter, like Janick Arbois, see in this short series of films a steady march toward “the perfecting, the deepening of an ‘extraordinary’ body of works, in the strongest sense of the word.” Arbois added moreover, “There is no secondary film in Bresson’s career,” his four films being “essential works of inexhaustible richness which will never be diminished by time.”

After A Man Escaped, Bresson continued to make films until 1983. Pickpocket (1959), a very free adaptation of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, is considered by some critics to be Bresson’s best film. It was followed by Trial of Jeanne d’Arc (1962), then by Balthazar (1965), a remarkable fable on life (and on evil) as seen through the stages of existence of a donkey.

From the viewpoint of style, Bresson’s films became more and more austere and metonymical with time. He forbade his actors, whom he called “models,” to act; they all had to speak their lines in a flat, inexpressive manner to disassociate them from theatrical style. He often favors close-ups or near shots of details which suggest the action rather than showing it directly. In an apparent nod towards the esthetics of classical French theater, he rarely depicts violence on screen.

While Bresson avoided filming violence, his last films are increasingly pessimistic, often focusing on death, particularly by suicide. Mouchette (1967), an adaptation of another work by Georges Bernanos, is about the rape and suicide of a young adolescent. A Gentle Woman, Bresson’s first film in color, begins by the suicide of a woman, followed by a long flashback in which her act is explained by the extreme difficulty of her relationship with her husband. After Four Nights of a Dreamer (1971), an adaptation of a novella by Dostoevsky, Lancelot of the Lake (1974) offers a stark, deromanticized version of the knights of the Round Table. The Devil Probably (1977) begins with the news of the suicide of a young idealistic ecologist and then proceeds to tell the story of his descent into despair. Money (1983), Bresson’s last film, is a severe story, with no background music to soften the blow, in which Bresson reflects on the relationship between the moral corruption created by money (greed) and violence.

Bresson passed away in 1999.Filmography

1934 Public Affairs (Les Affaires publiques, short subject)

1943 Angels of the Streets (Les Anges du péché)

1945 Ladies of the Park (Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne)

1950 Diary of a Country Priest (Journal d’un curé de campagne)

1956 A Man Escaped or The Wind Bloweth Where It Listeth (Un condamné à mort s’est échappé ou Le Vent souffle où il veut)

1959 Pickpocket

1962 Trial of Jeanne d’Arc (Procès de Jeanne d’Arc)

1965 Balthazar (Au hasard Balthazar)

1967 Mouchette

1969 A Gentle Woman (Une Femme douce)

1971 Four Nights of a Dreamer (Quatre nuits d’un rêveur)

1974 Lancelot of the Lake (Lancelot du Lac)

1977 The Devil Probably (Le Diable probablement)

1983 Money (L’Argent)