Setting

Mahler wrote his Third Symphony at a turning point in his life. The summer during which he completed his work, 1896, proved to be his last at Steinbach, but also came just before his monumental appointment to the Vienna Court Opera, the next year. His hut at Steinbach would help produce one last symphony before the triumphs and struggles of the years to come in Vienna.

Influences

At this point in his musical development, Mahler was enthralled by Des Knaben Wunderhorn, a collection of folk texts by Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano, compiled in 1806. Mahler was drawn to these texts because of their capacity to be both child-like and dark at the same time. It was this irony that Mahler saw in the nature surrounding him and in his own life (Solvik-Olsen 1990, 126). From this collection, Mahler culled two texts for use in his Third Symphony: Ablösung im Sommer and Es sungen drei Engel. By employing Des Knaben Wunderhorn, as he had alread in his First and Second Symphonies, Mahler took a small step away from Wagner, who never dipped into folk texts, choosing rather to exalt myths and heroes to his own Olympus. Mahler, on the other hand, sought to keep the texts with the land--to rearticulate, but not reorganize and appropriate. |

|

|

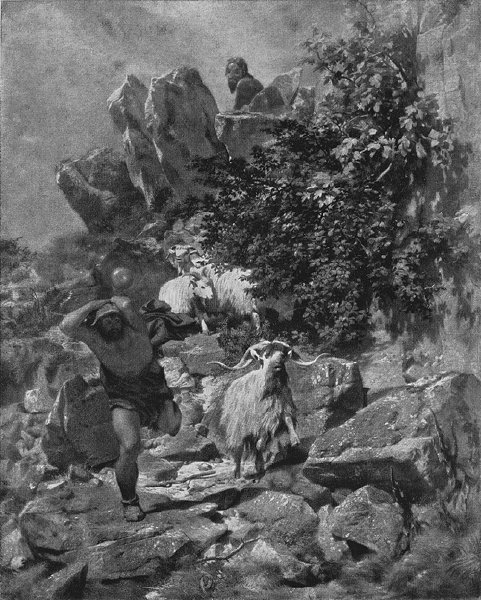

In addition to the Mahler's surroundings of mountain, lake, and forest, Greek mythology also played a great role in the formulation of the Third Symphony. The first movement, subtitled "Summer marches in: Procession of Bacchus," depicts the battle between the Greek satyr, Pan, and the god Bacchus, summer's armies alongside him. This was also a conscious choice, along the lines of Friedrich Nietzsche's theories on Apollonian (Wagnerian) and Dionysian art-forms. Whereas one stresses pure and strict ideals of the heart, the other proceeds in joy and bacchanalian ecstasy (Solvik 133). Nietzsche proves fertile ground for Mahler, also providing the text for the Symphony's fourth movement. |

Beyond all this, Mahler's fantastic and almost ecstatic aesthetic accords with another contemporaneous movement: the Viennese Secession. These artists, including Egon Schiele, Oscar Kokoschka, and Gustav Klimt, represented a rupture in the Viennese artistic establishment and also drew from sources like Greek mythology, nature, and Darwinian theory.