Movement II: "What the flowers of the field tell me"

Here we have what seems to be a trivial step in the creative sequence. From a Wagnerian perspective, flowers and nature in general would simply be something to be dominated and controlled. Yet in Mahler's philosophy, even the most miniscule parts of life deserve not only creation, but also redemption. Though they wilt and die through the seasons, they yearn to reach beyond themselves and be redeemed from this cycle of continued death (Solvik-Olsen 1990, 191). But the fact that mere flowers seek (and may receive) redemption is something well outside the bounds of Wagnerianism.

Movement III: "What the animals of the forest tell me"

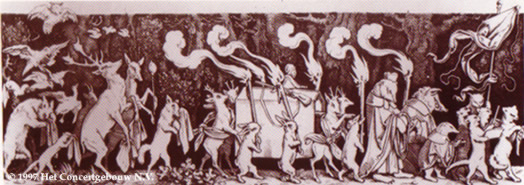

Make no mistake, though: Mahler's understanding of nature is by no means utopian. While he found extreme beauty in the world around him, he also found intense brutality. A reading of the third movement of the First Symphony proves telling for Mahler's approach to the animal world. That movement showcases a funeral march conducted by the forest animals for the huntsman, based on a popular woodcutting (see below). The irony in this scene is palpable, with the hunted how mourning the hunter. The funeral dirge in that movement, however, gives way to a less mournful and more joyous celebratory dance, presumably the animals letting their true emotions show. Animals value death differently than humans--the funeral march is but a sardonic parody of human rites (Solvik 196).

The third movement of this symphony proceeds along similar lines. The song Ablösung im Sommer (Relief in Summer) displays how the birds of the forest lament the loss of their entertainment during the hot season--the cuckoo.

Kuckuck hat sich zu Tode gefallen Ei, das soll tun Frau Nachtigall, [Wir warten auf Frau Nachtigall, |

The cuckoo has fallen to its death Oh, that should be Mrs. Nightingale! [We await Mrs. Nightingale, |

-- Original Text from Des Knaben Wunderhorn, author's translation.

Not only are these birds concerned with what will help them pass the time in summer, but they also have a bit of a secret. A closer reading of the last few lines reveals that the cuckoo is not yet dead at the time of the song! All the above lines in brackets are Mahler's words and are not original to the Wunderhorn text. It can only be assumed that Mahler intentionally placed these words in the song to put forth his views about the animal world and the macabre way it deals with death.

Man enters the scene

This movement is again split by intense dualities. Not only do we hear the animals' not-so-mournful song, but we also hear a human "voice" emerging from the woods. It is the post-horn solo that announces the arrival of man onto the scene. But curiously, this is not man-the-hunter, but rather a very different, reverent man-in-nature. Mahler based this musical entry on a poem by Nikolaus Lenau, describing a sudden stop in a postman's route to mourn the place in which his comrade fell. Here, the animals are silent, listening to this alien voice and alien approach to death. While they were irreverent and almost joyful, this call is simple and plaintive, tracing an Ab arpeggio and other notes within that scale.

At no point does Mahler emphasize an "ideal" in any part of his musical poem of nature. He presents nature as it is, both beautiful and brutal, and without the same regard for death as in the human world. But Mahler was very interested in the natural sciences of the day and wrote this music as a reaction to Darwinian theories of evolution. These theories had rocked the Western world in the last few decades in that they had displaced Man from his once God-given place above all nature (Solvik-Olsen 228).

Mahler sees this, but keeps Man separate from the animal through his capability to love, mourn, and be redeemed. He accepts that Man should exist in nature as a being not biologically superior to the rest.