Michael Armstrong vs. James Bond

That Arresting Rhythm:

- John Barry

- John Addison and Bernard Herrmann

- "A Visual Torn Curtain": Opening Credits

- The Murders

The

Breakup of Hitchcock and Herrmann

"Much Wiser Since My Goodbye To You" 40

After over a decade of collaboration Hitchcock and Herrmann were probably bound to part ways eventually simply due to egos and difficult personalities. However, even though Universal suggested another composer for Torn Curtain in order to avoid the financial failure of Marnie, Hitchcock wanted to work with Herrmann again on this film, though he was rather dictatorial about the importance of a marketable love theme and

“the need to break away from the old fashioned cued-in type of music that we have been using for so long” 41.

In fact, Hitchcock was so determined to have a new style of score for the film, and so concerned about his authorial control, that he had production associate Paul Donnelly write to Herrmann, saying

“Benny, there is one point that Hitch asked me to stress and that is the fact that you should not refer to his ‘views’ toward the score, but rather his requirements for vigorous rhythm and a change from what he calls ‘the old pattern’” 42.

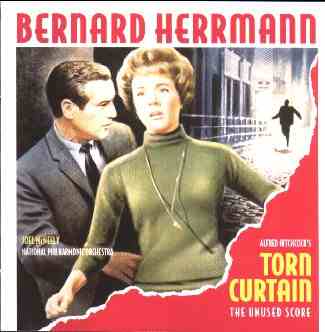

Herrmann complied, writing for “outlandish and unusal orchestration” compiled of French horns, flutes, trombones, tubas, timpani, cellos, basses and a small group of violins and violas. The composer was relying upon the primary disjunction of the brass and woodwinds to create “a steeliness and aridity” to match the muted, gray cinematography. Hitchcock, however, after seeing part of the scored film, claimed that it was not at all what he wanted, despite the dramatic, pulsing nature of the score built on simple repeated and inverted scales 43. Herrmann, in response to the director’s assertion that “he was entitled to a great pop tune” commentedr

“you don’t make pop pictures. What do you want with me? I don’t write pop music." 44

Despite his logic, Herrmann was fired and replaced with John Addison, recent Academy Award Winner for Tom Jones, who scored the film, like Bond films, using leitmotifs. In a futile attempt to create the marketable pop song, Addison joined with Jay Livingston and Ray Evans to write “The Green Years,” which Hitchcock ultimately decided not to use 45. Thus not only did Hitchcock fail to produce a film with a commercially viable soundtrack, he also failed to produce a film with a decent score altogether and broke up a great artistic team.

Addison's score for the film is lush, with elaborate orchestration and at times overemphasis of a dramatic point. One such example appears with the introduction to the Hotel D'Angleterre in Copenhagen. With the establishing shots of the city and the hotel, Addison writes a chipper cue of violins and winds that begins by sliding up in pitch to a comfortable, major key. With the cut to the interior of the hotel lobby, a single brass instrument comes in to play Hitchcock's television theme song, indicating musically Hitchcock's cameo (and taking all the fun out of the game). After the first phrase of the TV theme, Hitchcock picks up the baby on his lap and shifts it to his other knee while strings and chimes spiral upward with the lifting of the baby and as he sets the child down again, the second phrase of the TV theme appears. Techniques like this rightly cause Royal Brown to call the music "Addison-scored fluff" 46.